Drippings from the Honeycomb

More to be desired are [the rules of the Lord] than gold, even much fine gold; sweeter also than honey and drippings of the honeycomb. (Psalm 19:10)

Christmas has always been celebrated like we presently experience it, correct? History shows a varied tradition from no celebration to celebration. APOSTLIC (AD 33–100) Matthew and Luke dedicate two chapters to the infancy stories of Jesus in their Gospels to show how Christ fulfilled OT prophecies. John stressed the significance of the Incarnation, “the Word became flesh.” However, during the first century the Church did not celebrate Christmas. Emphasis was placed on the Lord’s Day as a weekly remembrance of the Resurrection, which was commemorated annually at Passover. PATRISTIC (AD 100–500) The Apostolic trend continued. Many early Christians even opposed remembering the birthdays of martyrs or Jesus seeing their death as their birthday. The first record suggesting the date of Christ’s birth as December 25 was in AD 221 by the Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus. (Previously it had been remembered in conjunction with His baptism on Jan 6. Some eastern churches continued to observe this but eventually Dec 25 became the majority view). Several explanations have been offered:

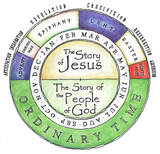

That Christmas replaced pagan festivals is further evidenced in when the first Christmas is recorded. It was in Rome in AD 336, after Constantine had made Christianity legal and even the favoured religion of the Empire. As a result the 4th century saw a “powerful trend towards a greater use of ritual and ceremony.” (NN1.97). From Rome this new ceremony spread, attested by numerous 4th century sources. Christmas is two words: Christ and missa; Latin from the worship service’s closing prayer meaning “go” or “send” (i.e. mission). Having celebrated the birth of Christ Christians went out to proclaim the glad tidings of His coming. Still Christmas was a smaller festival compared to the Passover/Easter and the growing traditions of Holy Week and Lent until the 9th century when it attained its own liturgy. Christological debates also helped to cement the importance of Christmas (e.g. Chalcedon, 451) MEDAIEVAL (AD 500–1500) Festivals surrounding the remembrance of Christ’s birth proliferated during the Middle Ages. The basic pattern was present by AD 600: Advent (24 days before Christmas, c. 500s), Christmastide (12 days of Christmas beginning Dec 25–Jan 5), which ended with Epiphany, Jan 6 (wise men). Christmas became part of the elaborate series of festivals to saints and other holy days. The development of a Church year or calendar was ‘complete.’ Gifts were first given in the 1400s. REFORMATIONS (1500–1600) At the Reformation Lutherans and Anglicans modified and simplified the celebration of Christmas but retained it (e.g. Martin Luther wrote ‘Away in a Manger’). The Reformed, Puritans and Presbyterians did not celebrate Christmas. They saw it as a Catholic tradition with no warrant in the Bible. They followed the regulative principle. POST-REFORMATION (1600–1700) Parallel traditions, some celebrating Christmas and others not continued amongst Protestants. Puritans in England and New England banned Christmas altogether. Baptists were part of this tradition who until the late 1800s did not celebrate Christmas. Still, within the Dissenting tradition new carols were written like Isaac Watts’ ‘Joy to the World’ (Congregationalist) and ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing by Charles Wesley (Methodist). From hymnbooks some Dissenters sang at least some carols around Dec 25. Gift giving also increased during this period. MODERN (1800s–1900s) For many Protestants, the presence of high-church traditions coupled with Romanticism (feeling and expression), biblical liberalism and the softening of denominational traditions due to deconfessionalism all contributed to a rise of the celebration of Christmas in traditions which hadn’t previous placed great or any emphasis upon them. The Victorian age was one of expression. Carols proliferated. Cards were given (first commercial, 1843). Industrialization made affordable gifts available, beginning the commercialization of Christmas. The Christmas tree, which had been a German tradition dating to the 1500s, was brought into England from the Germany by the Prince Consort (1848) and made popular by Queen Victoria. Given Germany was one of the later European nations to be evangelized there is an evident link to medieval paganism, and even tree worship in ancient paganism. Slowly trees made there way into church sanctuaries. Perhaps the largest change to Christmas during this time relates to the mythical figure of Santa Claus. Rooted in Saint Nicolas with pagan embellishments, through commercialization, the man in the big red suit co-existed beside Christ, often even in Christian circles. Many of these trends continued into the 1900s; culture and Christianity co-existing and often being tightly interwoven, Christmas culminating on the 25 rather than the 6th of January. POST-MODERN (late 1900s–2000s) By the late 1900s it became clear Christ had been forced out of Christmas. Some advanced ‘political correctness’ such as “happy holidays.” Christmas was now about Santa and gifts and family. ‘Keep Christ in Christmas,’ was the slogan of conservative advocates. REFLECTION Christmas is not inherent to Christianity but was developed, along with associated symbolism, over 1700 years. One of the blessings of the Post-Christian scene is that it is ripe for reflecting upon Christian beliefs and practices (ecclesia semper reformanda est, the Church is always to be reforming):

Bibliography Oxford Dictionary of Christian History Encyclopaedia Britannica Nick Needham, 2000 Years of Christ’s Power Comments are closed.

|

Featured BlogsLearn about Jesus Author:

|

LocationPO Box 73,

144 Lorne Street, Markdale N0C 1H0 |

Join by zoom |

Contact us |

Donate |

|